After the collapse of ISIS in Iraq and Syria it would be a mistake to think that the trade in artefacts looted from areas of conflict – often called blood antiquities – has suffered the same fate.

Reports indicate it to be the third largest illicit trade in Europe though conclusive estimates are difficult. How much that particular terrorist group profited is unclear but in the scale of destruction and looting – amounting to what some call “cultural genocide” – it was used as a weapon of war.

Crime, cash and conflict

Tackling the illicit trade in antiquities is therefore as much about preventing war and terrorism as it is about fighting international money laundering and organised crime. This mixing of hazards – crime, cash and conflict – is what the EU-funded Global Facility on AML/CFT hopes to address as it draws together knowledge and expertise to curtail the illicit trade in antiquities and the dirty cash it attracts and generates.

Terrorist looting from what was ancient Mesopotamia represents the latest episode in a story of cultural theft that stretches back centuries and spans the world. Often it is assumed that demand is driven by European and North American buyers but research shows that markets are emerging in Iran, Turkey, the Persian Gulf States and their neighbours. 1

Reports indicate [blood antiquities] to be the third largest illicit trade in Europe

Money launderers and terrorists go to antiquities for several reasons. First, demand outstrips legal supply so that the trade offers high rewards. It is a market where private collectors can peak prices to eye-watering levels, as in the controversial sale of the quartzite bust of king Tutankhamun at auction in 2019 for almost €5 million.2 In contrast to illicit drugs, antiquities straddle the bounds of legality, with only the expert – and rarely the customs official or well-intentioned purchaser – able to distinguish the loot from the legitimate.

Second, it is especially easy to turn a blind-eye in an industry notorious for anonymous buyers, private sales and cash payments – the latter vulnerability was one of several the European Union sought to tackle with its 2018 Anti-Money Laundering Directive 3. On the other side of the Atlantic, the US art market has woken up to the scale of the problem too.

Last year a non-partisan thinktank released a report recommending an array of actions be taken by the art industry, financial sector and government.

“Initial looting is often facilitated by terrorists or armed groups, he says, and then organised crime take over as experts in exploiting vulnerabilities in cross-border trade routes, including bribing customs inspectors.”

Organised crime groups “wash” looted antiquities by putting both evidentiary and geographical distance between source and sale, often using circuitous transit routes, says Tim Hanley, a former police officer and law enforcement adviser to the EU’s Global Facility on AML/CFT.

But it may also be a problem for clean yet unaware officials and dealers too. In the case of trade-based money laundering, where only the world’s experts know the value of specific coins, paintings, vases and other archaeological treasures, misinvoicing and tax evasion is all too easy. Experts at major auction houses try to play their part in instituting due diligence. Nevertheless, archaeologist Michael Danti, in testimony to the U.S. Congress, described the global art market to be “highly opaque, fragmented, and relatively unregulated at all levels.”

Online art sales: the new loophole

Most unregulated of all are online art sales, which have showed signs of growing. Research into almost a hundred Facebook groups established to traffic antiquities found an interconnected network of group administrators managing almost 2 million members around the world.4

Among Syrian-based Facebook groups a third of users offering artefacts were identified to be based in conflict zones. Social media, and other more discreet online platforms, enable the seller and buyer to transact without the middlemen usually associated with international smuggling.

Online or offline, transnational criminal networks are heavily involved in trafficking antiquities alongside the illicit trades in people, drugs and arms. Law enforcement continues to disrupt the trade. Last year, an operation led by Interpol and the World Customs Organisation, together with law enforcement from seven countries, resulted in the seizure of almost 9000 cultural objects and over a hundred arrests.5 Tracking online sales in cultural artefacts spawned investigations that covered 103 countries. This level of international cooperation also opened up 300 new investigations that have the potential to disrupt a maze of criminal networks and illicit money flows in the coming years.

Cultural theft: what we can do about it

Tim Hanley sees a twin approach for the Global Facility in helping to break-up organised crime networks and discouraging the illegal market in antiquities, building on existing efforts by law enforcement agencies and from within the sector. In recent years as awareness has grown, rules have been tightened. European Union legislation has increased pressure on sellers to carry out due diligence to verify provenance before sale. Although prestigious auction houses, who trade on their reputation, have a strong incentive to clean out their catalogue, even they struggle to consistently identify stolen artefacts. 6

And despite their headline-grabbing sales it is in the middle segment of the market, made up of smaller auction houses and private dealers, where the majority of sales takes place.

For a long time it has been recognised that detection and due diligence only goes so far to counteract the systemic risks in the flow of illicit cash and goods. In UNESCO’s 1970 Convention and UNIDROIT’s Convention twenty-five years later international will was transformed into legal measures to protect the cultural heritage of states that had recently gained independence in Asia and Africa. The 1998 Washington Principles on Nazi-confiscated Art offers another interesting precedent for how international commitments, albeit non-binding, can be established to identify, register and return Second World War loot.

One significant aspect of the 1998 Principles was the participation of thirteen international NGOs, museums and auction houses, alongside more than 40 governments. Establishing international measures to protect local art and culture artefacts – and cut-off a source of criminal and terrorist funds – is of both public and private interest. Hence, consensus must involve a wide array of organisations to be effective.

Cultural heritage continues to be looted amidst conflict. After the outbreak of war in Yemen in 2014 and over the following years the smuggling of looted antiquities to the USA leapt dramatically.7

Antiquities looted in former conflicts often stays in circulation. Sometimes, items are identified and returned back to their country of origin, as was the case of a 2,400-year-old artefact, looted during Lebanon’s civil war, which was spotted by a New York museum curator almost forty years later and returned to Beirut.8

There are several databases of missing, forged or stolen cultural property which can help to identify and return stolen items. The Leonardo database, which has registered 6 million works of art, is run by the Carabinieri and recovered an estimated €450 million in stolen art by 2014.9 Another database proactively registers cultural items held in museums and sites in areas of conflict in anticipation of the risk of looting.10 Recognising the fragmented nature of data on this topic and the difficulties that presents to investigators the Global Facility will be improving systems for information sharing.

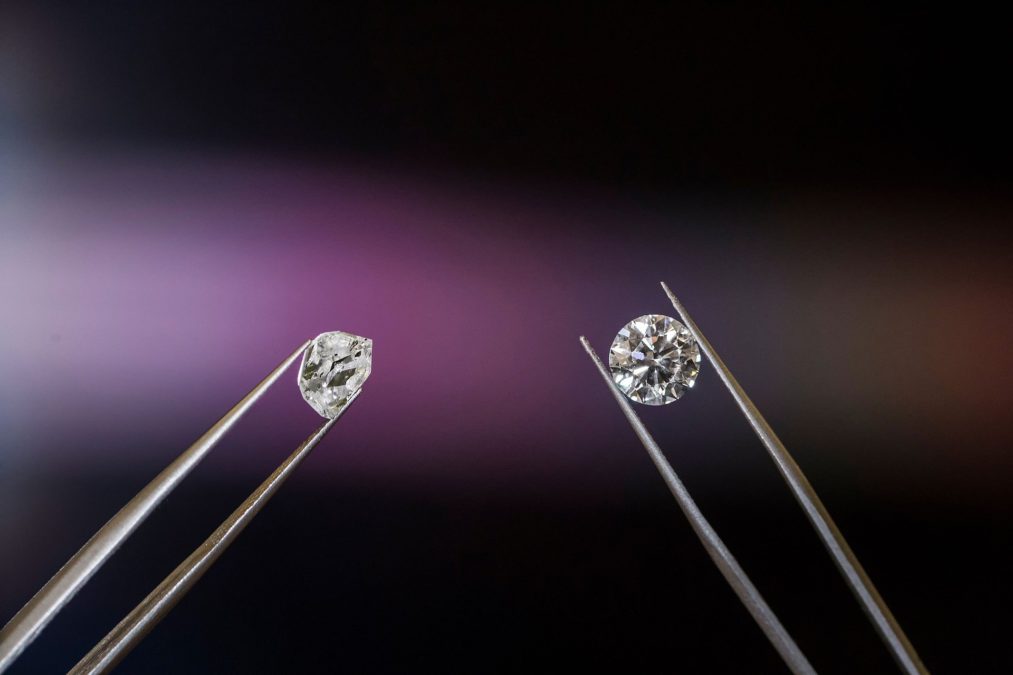

Learning from bans in the timber, fur, ivory and diamond trades is informative too.

Analysis of the Kimberley Process, which successfully banned conflict diamonds, made comparisons to the particular systemic vulnerabilities in the art trade.10 One option it highlighted would require proof of legality before art or artefacts enter legal trade channels, reversing the current burden involved in proving guilt.

Man-made art offers a unique set of challenges but consumer awareness and pressure has the potential to strengthen standards and overhaul the entirety of the supply chain in the art and antiquities sector too. As Donna Yates, a leading experts in illicit antiquities says,“If you have a big ivory object at the dinner table, your friends are thinking ‘dead elephant’”. The question remains whether a similar mindset can make buyers of antiquities think twice, preventing a trade in which criminals and terrorists profit from cultural theft.

1. Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open Source Data, RAND, 2020

2. Bust of Tutankhamun sold at auction for £4.7m despite Egypt protests, The Guardian, 05.07.2019

3. European Union tightens anti-money laundering rules in the art market, The Art Newspaper, 30/04/2018

4.Facebook’s Black market in Antiquities, Athar Project, 2019

5.101 arrested and 19,000 stolen artefacts recovered in international crackdown on art trafficking, Interpol, 06.05.2020

6. “Due Diligence”? Christie’s antiquities auction, London, Trafficking Culture, October 2015

7. ‘Blood Antiquities’ Looted from War-Torn Yemen Bring in $1 Million at Auction, Live Science, 05.06.2019

8. Ancient statues looted in Lebanese war returned decades later, Reuters, 12.01.2018

9. Using databases to combat trafficking, Future Learn

10. Do we need a Kimberley Process for the Illicit Antiquities Trade?, Trafficking Culture